Data Description

For this project I chose to look at the 1883 Pensioners. I wanted to explore a data set that involved some aspect of war but with a different twist. When we look at war data it is usually casualty figures that are the main topic of discussion. People forget that for those that are wounded and the families of those killed in action, some sort compensation, a pension, is given as a way of saying thank you for your service and to help alleviate the difficulties that may result from their time in the service. The reasons for the pension can be anything from visible wounds, to psychological trauma, to the loss of the head of household—the breadwinner.

When looking at any given data set, you are almost certainly going to be given numeric data, textual data, and/or geographic data in some quantity. In regards to the 1883 Pensioners data set we are given all three. But, each is represented in a different amount. The textual data is on a very large-scale, as is the numeric figures. There are dozens and dozens of different categories for wounds. From gunshot wounds, to diseases and illnesses, to amputations, to being widowed, the list is extensive. We are also given the names of each person and the month and year of the first pension claim.

For each category that is listed, a number of sub-categories of numeric data is also given. The most interesting of which comes in the form of the monthly rate of payment received by the individual. With this number you can then twist it around to see the average monthly rate, the median monthly rate or the monthly sum. What this allows someone reading this data to do is to compare and contrast the various pension claims to see how they stack up in severity, in terms of monetary compensation. Another aspect of numeric data is seen in the number of records of each pension claim. This too allows us to see what the largest pension claim was.

Geographical data is present in this data set. However, an address is not given. Instead, it is referred to as “Post Office.” This is the city or town that the individual is currently living in at the time of pension submission. This does not provide much in terms of useful information as this list includes individuals strictly in the Capital region. If an address had been provided, we could then create a map of the city of Albany along with the various outskirts and examine just where these veterans or their families are living. Are they generally in poorer neighborhoods as is the general trend with war enlistees? Is it an area that is higher concentration African-American or Caucasian? Unfortunately, when this list was compiled they were not expecting someone to look at it decades later and attempt to create patterns and trends from it. No, it was instead meant to organize those that were receiving government pensions for their role in the Civil War.

Data Visualization 1

For my first visualization, I wanted to take a look at the number of records for claiming a pension. In this visual we will be looking at the “Number of Records” tab.

At first glance it does not look like much. I wanted to create a story that correlated with the figures that show that most of the deaths associated with the Civil War were in fact, not combat related. When I say combat related I am talking about gunshot wounds, hand-to-hand combat and artillery barrages. Instead, the number one killer of soldiers, on both sides, was dysentery (www.civilwar.org). Most of the soldiers that fought during the Civil War were from the rural countryside. They lived their lives on small mom and pop farms and interacted with only a handful of other people outside their community. When you do not have much contact with significantly larger groups of people, your immune system becomes more susceptible to contracting diseases and illnesses that others, from a city for example, would not come down with. For this reason, a substantial number of the deaths during the war were from disease as these farmers interacted with hundreds and thousands of other men for the first time. Other illnesses include smallpox, malaria and chicken pox. Because the medical field had not advanced to the point of having proper medicine to treat this diseases and viruses, large outbreaks were not uncommon with both the Union and Confederates.

While it was my initial goal to show this pattern in my data set, the opposite, in fact, developed. Now before going any further I need to emphasize something about this data set. This data is not an accurate representation of the makeup of soldiers in the Civil War, on either side. It is a rather small sample size of just under 1,000 claims. A claim does not necessary entail that they played a direct role in the Civil War, rather it could be the family applying for a pension for a deceased family member. In looking at the data in the “Number of Records” tab, we see that the largest number of claims fall under the category of Mother/Father/Minor, followed by General Wounds, Gunshot Wounds, Loss of Limb due to Combat, Disease, Injuries, Other, and lastly Amputations. According to this graph, there were a total of 918 records. 408 of these fall under the category of Mother/Father/Minor and only 51 falling under Disease. This data set is telling a different story than what the national story is. Instead of having most of the cases be relegated to be disease related, they are instead a second-party claiming the pension, for example a widow. The General Wounds are second with 215 respective cases, these being injuries as a result of chopping wood or breaking a bone. While there is a significantly large difference between claims as a result of disease or illness and being widowed, it can be safely assumed that a portion of the widowed claims are a result of their loved one dying from some sort of disease.

Process Documentation 1:

All of the groups that are represented in all my visualizations have numerous sub-categories within. For example, if you look at the Gunshot wounds bar, what you have is different types of gunshot wounds making up the 119 total claims. There are gunshot wounds to the head, face, jaw, left leg, right foot, etc. This visual is fairly new. When I first set out on this journey, this particular example was not composed of a neatly grouped list. Instead, I had every single different type of gunshot wound, disease, illness; you think of it and I probably had it listed. Now you would think that the process to create categories to house all the various wounds would be fairly simple. Well, you would be dead wrong. You see, when each reason for filing a pension claim was originally listed, there was no universal language or code to organize things. It was all dependent on the person writing at that moment. Each person had their own unique abbreviations and wordings for various items. This meant that some reasons could be grouped under more than one category. After I was able to discern what should be placed where, I chose to use the default colors that were given to me each time I dragged the “Grouped Wounds” Dimension into the table. These colored groups represented my columns. Next, for my rows, I decided to utilize the “Number of records” measure to show the amount of claims filed in each bar. It was not complete but to further show the differences between each column, I chose to show bars with higher amounts of pension claims as larger in width than those with much smaller amounts. While this makes sense, in practice it can create a problem in viewing such thin bars.

Argument 1:

As I mentioned earlier, the main argument for this particular visualization is that disease and illness were not a particularly large contributor to pension claims, in terms of this data set on the Capital region. Poor hygiene along with interacting with large groups of other soldiers resulted in numerous cases of malaria, dysentery, etc. Outbreaks within regiments were not uncommon and men would often be forced to leave the service to due being sick. This is backed up the need to apply for a pension. Because the people listed in this census are from a highly populated region in the northeast, for the most part at least, their immune systems have been able to build up some sort of tolerance to the various illnesses out there. I would argue that this is the main reason for the low numbers of disease and illness claims filed by these men and their families. This assumption is supported by looking at other pension records that are available (Google Books: 291-303). For example, if we were to look at the city of Utica in Oneida county, we would see a rather large list of wounds that pertain to injuries sustained in battle or by other means. While there are cases of diseases and illnesses, they are trumped by the various wounds. We can also look at the town in which I grew up in, Clinton, also in Oneida County. By today’s standards, Clinton is a very small village. At last check, the population was just under 2,000 so we can only imagine how much smaller it was over 150 years ago. Out of the list of pensions for Clinton, there is only one entry that claims an illness: dysentery which was the number one killer during the Civil War. But the remaining entries are either combat related or because a widow or family member is claiming the pension because they lost a family member in the war. The north was much more populated than the south during the war, same goes today as well, so it makes sense that most of the pensions were in response to wounds other than disease and illness. If you look at South Carolina, (Google Books: 184-189) a startling trend emerges. Here we see the opposite of the north. Instead of mostly gunshot wounds, we see an overwhelming number of widows and illnesses. This can be explained by the sheer number of southern males that were lost during the war as a majority of the fighting took place in the south. The south is also nearly exclusively rural, hence the hundreds of plantations, so the increase in illness cases can be explained by the weaker immune systems of the Confederate Army.

Data Visualization 2:

For my second visualization I chose to examine the role of women during the Civil War. While women have always played key roles in every conflict the United States has fought in, the exact extent to how much they can be involved has always been controversial. Only in the past few years has combat roles been opened up for women to be involved in though they are required to pass the same physical requirements as their male counterparts. But during the Civil War women played a much more behind-the-scenes type of role. Most often referred to as Camp Followers, these women did exactly as their title suggests: they followed the train of soldiers. These were women who, generally, did not have much at home after their husband, brother, father, etc., went off to war. If they had no means to sustain themselves and make money, they often followed their loved ones as they went off to war. They acted as cooks, nurses, cleaners, and prostitutes. Some even went as far as dressing up as a man (Sam Smith) and fighting on the front lines, some even died (www.civilwar.org). While they no where were close in numbers as the men, it is believed that around 500 women secretly fought in the war. Probably the most famous woman fighter is that of Jennie Hodgers, better known as “Albert Cashier” (Civil War Trust). She enlisted in the 95th Illinois Infantry on August 6, 1862 and would go to fight in over 40 different engagements. It is also believed that at one point she was captured by the Confederates but she broke out of prison and returned to duty. She served three years before her unit was discharged for heavy losses due to combat and illnesses. But her story does not end here. She went on to continue living under the guise of a man, collecting a pension, and would only be discovered in 1910 when she was hit by a car, though the hospital kept her secret quiet. However, 3 years later, as dementia set on she was discovered and forced to live the remainder of her life as a female. She would die 2 years later and be buried in her uniform with full military honor.

Process Documentation 2:

The creation process for this visual is nearly identical to the first. The main differences here are the different dimensions and measures that were used. I chose to have a horizontal graph for this one in order to break the data up into male vs. female. In terms of data, I included type of injury sustained, the average monthly payout and the number of cases for each category. As with the first visual, I created larger bars for the categories that included larger number of records and smaller bars for the categories that included a small number of records.

Argumentation 2:

As I have mentioned earlier in the first visual, this data set is a rather small sample size. To accurately create a significant argument, we would need to also be graphing other 1883 pensions from nearby counties. Luckily, Albany county seems to have had its fair share of females taking part in the fighting during the Civil War. Whether they were injured while fighting or were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time as a camp follower is impossible to know for they may have never been discovered. In any case, what we have in our data set is 2 records of females sustaining gunshot wounds and then gaining a pension as a result. In scouring the nearly 1,000 entries, I was unable to find their names which may have led to further research and possibly finding out if they had in fact disguised themselves. Nevertheless, these two women received an average pension of $4.00 a month compared to her male counterpart whom received an average of $5.93. The sample size is way too small and distorted in favor of the men with 117 records of gunshot wounds so it is difficult to say whether they received such a low amount because they were women or because their wounds were not as severe as some of the men. In any case, they did in fact receive a pension for gunshot wounds. Even if we take out the gunshot wounds from the data, historians know for a fact that women played a key role in the Civil War. Clara Barton herself, founder of the Red Cross, was a nurse during the war. Women took on every aspect of the war that the men did including fighting and performing dirty tasks such as amputating limbs. While historians acknowledge their contributions, I do not believe classes teach how much women played a direct role in the war. Up until the Fall of senior year in college, I was unaware of the camp followers. To show that they played this large role in the war, we should be teaching more about them.

Further research Questions:

- Were pension claims during the Civil War and claims 20 years after the end of the war greatly differ in terms of monthly payments for similar injuries?

- To figure this out I would rearrange the data set in chronological order. I attempted to do this but my efforts were futile as I could not figure out how to correctly get Tableau to do it. With a lot of time on my hands I suppose I could create an Excel spreadsheet that is in chronological order and could even uncover more patterns in the data that we are unable to see otherwise.

- Did the pensions differ based on whether you served as a Union soldier or a Confederate?

- In a preliminary scour of the Arkansas, Missouri, and South Carolina pension rolls, this would seem to not be the case. No matter the wound, you received nearly the same amount whether or not you were a northerner or a southerner.

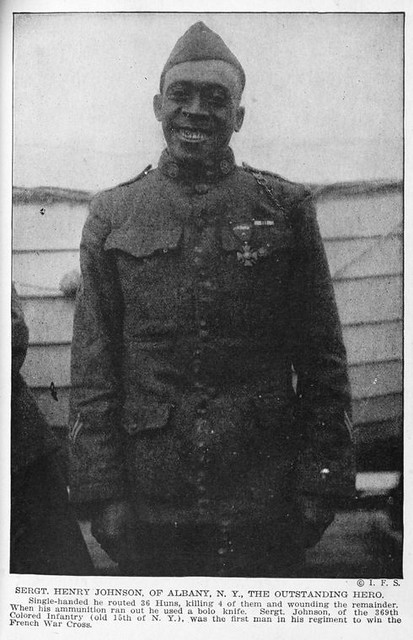

- Were African-American veterans afforded the same treatment by the Pension Bureau?

- When I first chose this data set, I was under the belief that this was a list of African-American soldiers and their families that were receiving pensions. I quickly learned the opposite, that it was probably whites that represented the bulk of the data. That is not to say that African-Americans are not present on the list, however I would imagine if they were a significant contributor to the war effort (which they were), wouldn’t the Pension Bureau have a separate column for race? Every 1883 Pension roll uses the same layout with the name, record number, cause for pension, etc. None of them include the race of the individual. So this begs the question of if they just did not deem that important enough to distinguish in the records or did they just not offer any pensions to African-American veterans. This would, of course, violate the 14th Amendment. I would bet that with some more digging, one could uncover the records of African-Americans receiving pensions, I just do not know where to look for that.

Bibliography

“620,000 Soldiers Died during the Civil War, Two-thirds Died of Disease, Not Wounds: WHY?” Civil War Trust. Accessed May 11, 2016. http://www.civilwar.org/education/pdfs/civil-was-curriculum-medicine.pdf.

Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed May 12, 2016. http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/jennie-hodgers.html.

United States Pension Bureau. “List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883.” Google Books. January 1, 1883. Accessed May 11, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=aLkqAAAAMAAJ.

United States Pension Bureau. “List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883.” Google Books. January 1, 1883. Accessed May 12, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=t7oqAAAAMAAJ.

Smith, Sam. Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed May 12, 2016. http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/untold-stories/female-soldiers-in-the-civil.html.